The “Check The Back Shelf” series returns with another look at the weirder world of cinema that video stores provided beyond the “New Releases” section. These unusual treasures were in the back of the shop, tucked away from the casual movie fans. B-movies, horror, foreign films, and rare bootlegs were just some of what was waiting there to be discovered.

by Matthew Essary (Twitter: @WheelsCritic)

The regional cinema of Hong Kong, at one time, was said to produce the best action films ever released. Hong Kong filmmakers used inventive staging and a heavy focus on stunt and fight choreography, putting those aspects on equal footing with the other elements of constructing a film, like casting and editing. It was not unheard of for the crafting of these scenes to take up the bulk of a film’s shooting days. This commitment to creating thrilling sequences led to the phrase “Hong Kong-style action” being used as high praise for any film intended to thrill an audience.

The hyper-kinetic style of cinema the Hong Kong film industry produced inspired homages and in some cases outright theft, from the late 1970s well into the 2000s, by filmmakers from other countries. Japan, India, and especially the United States looked to the small Chinese island for ways to make their own films bolder, more action-packed, and as emotional as the brisk (most around 90 minutes) films that Hong Kong put out in the hundreds during their most productive periods.

I could spend hours listing all of the references, borrowed techniques, and concepts that were lifted by outside filmmakers from what Hong Kong was doing in their regional film scene in that 30 year period. The most infamous example of this, however, goes to a familiar name in this column, Quentin Tarantino. The wildly popular filmmaker has long been vocal about his love for Hong Kong action films and references to them are littered throughout his filmography. What makes one example of his Hong Kong influences more infamous than all the others is that the it led to him creating what is essentially a full remake of another film. Tarantino’s breakout film was the 1992 crime tale RESERVOIR DOGS. The entire plot (and multiple scenes) were pulled directly from a successful 1987 Hong Kong film called CITY ON FIRE. That film was directed by a man named Ringo Lam.

For years, films fans who wanted to appear knowledgeable would bring up how Tarantino stole much of his debut feature from Lam’s bleak and gritty tale of the blurred lines between cops and the robbers they chase. An even smaller subset of fans know that Ringo Lam had done a similar thing himself years before. You see, Lam had reversed the paradigm of influence. He had taken a successful American film and used its basic elements to make a distinctly Hong Kong-style movie.

The movie he chose was the 1985 film WITNESS (starring Harrison Ford and Kelly McGillis). He took Peter Weir’s tale of an injured detective uncovering police corruption in an effort to protect a young Amish witness, while hiding out among the boy’s rural community, and transformed it into a story of a Hong Kong cop working to solve a murder where the only witness is a young girl born to a mainland Chinese family. That film became 1989’s WILD SEARCH.

It would seem at first glance that Lam had removed the most distinctive aspect of the story, the rural Amish, from his take on the material but nothing could be further from the truth. You just have to know a little of Hong Kong’s history and its effect on the pop culture there to understand the similarities. Before 1997 the island of Hong Kong was fully under British rule and this was in stark contrast to the rest of China, the ‘mainland’, where communist rule was in full effect. This governmental divide led to the people of Hong Kong looking down on their less fortunate countrymen from China proper. In entertainment intended solely for Hong Kong and British enjoyment, the people of mainland China were often portrayed as poor, uneducated, and less ‘worldly’ than their Hong Kong counterparts. They were “others” to the people of Hong Kong, just as the Amish feel otherworldly in Weir’s film.

Chow Yun-Fat and Harrison Ford

Chow Yun-Fat and Harrison Ford

In Harrison Ford’s place, Ringo Lam cast actor Chow Yun-Fat (CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON). Chow (in China the surname is listed first) had just a few years prior broken out of the television soap opera scene in Hong Kong with a string of action hero roles, including the aforementioned CITY ON FIRE. Unlike a lot of his contemporaries, Chow was not a trained martial artist and had no background in stunt work. His heroic leading man persona was based on a suave and cool demeanor that more closely resembled the leading men of classic Hollywood than the physical intensity of someone like the late Bruce Lee or the imaginative physical action-comedy of Jackie Chan. The casting of Chow Yun-Fat in itself gives WILD SEARCH a much different feel than the original WITNESS. Chow’s easy going, classic movie star charisma could not be more different that Harrison Ford’s portrayal of a world weary policeman.

Chow’s counterpart in the film, the McGillis to his Ford, is Cherie Chung. Chung began her entertainment career after placing highly in the 1979 “Miss Hong Kong” beauty pageant. Pulling fresh faces from pageants for use in television and film has always been a common occurrence in Asia. Many times, the results can be cringeworthy as modeling and beauty do not always translate to screen presence and acting ability. Luckily, in Chung’s case, she was a natural acting talent who had palpable chemistry with her costar in Chow Yun-Fat.

Cherie Chung and Kelly McGillis

Cherie Chung and Kelly McGillis

The chemistry between the two leads of WILD SEARCH is a necessity, as much like the original WITNESS, their budding romance forms the backbone on which the rest of the film is built. They have a much more overt courtship than their western counterparts and these parts of the film are sweet and enjoyable, for example there is a scene where the two are stranded on the side of the road that ends with them playfully embracing that has the sort of easy warmth and charm that is just barely touched on in WITNESS. What really sets WILD SEARCH apart from WITNESS though is how it approaches its action elements.

In WITNESS, the instigating crime is the murder of a man by corrupt policemen in a train station bathroom. The scene in question is quick, violent and reminiscent of Italian Giallo films and after this point, there is surprisingly little action to be seen. Ford’s character, John Book, engages in a brief shootout that leaves him wounded and sent into hiding with the Amish community that the titular young witness resides in. After this scene, however, there is no more traditional action until the villains discover his whereabouts and descend upon the peaceful, rural community for the film’s final confrontation, and even here the action is slight at best.

In WILD SEARCH however, the instigating crime involves a shootout amongst gun runners and the “Hong Kong-style” is on full display as bloody squibs and debris are rampant when the bullets start flying. There are other chaotic guns fights and tense car chases throughout the film’s brief runtime to hold your attention as the romantic elements unfold around these action moments. Added to the mix is the inclusion of small bits of comedy mined from the relationship between Chow and his police associates gives the film a fun combination of flavors that keep it lively, where at times WITNESS is a little stilted and self-important. WILD SEARCH aims to simply entertain and does a fine job. It also avoids the slow patches of its predecessor by not dwelling on the daily life of the mainland Chinese transplants. WITNESS occasionally feels like it stops dead in its tracks to present a documentarian-style look at Amish living.

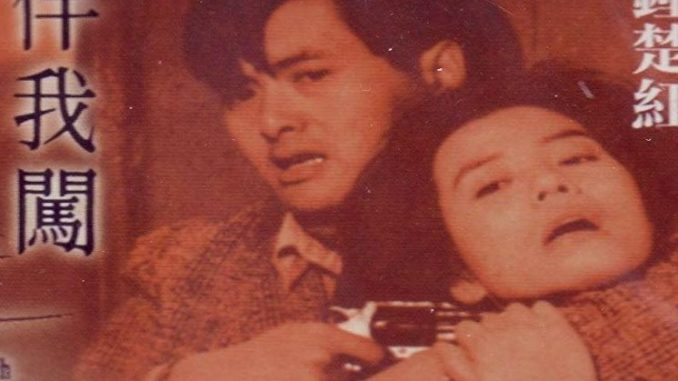

A theatrical poster for WILD SEARCH

A theatrical poster for WILD SEARCH

WILD SEARCH’s desire to simply entertain its audience is never more apparent than in the finale of the film where, as in the original WITNESS, the bad guys descend upon the rural community for a confrontation with our protagonists. Here again bullets, and squib explosions are plentiful culminating in a breathtaking bit of stunt work where, Chow Yun-Fat is trapped in a fight with the main villain in a burning building and ends up being set on fire without the use of a stuntman! It’s an amazing stunt that clearly put the star of the film at risk and never would have been possible except in the world of Hong Kong action filmmaking.

What sticks with me most though about WILD SEARCH is the same thing that I carried away from WITNESS – the performances and chemistry of the leads. It reminds me of a great quote from legendary film critic Roger Ebert:

“it’s not what a movie is about, it’s how it is about it.”

Comparing Ringo Lam’s WILD SEARCH to WITNESS illustrates that concept perfectly. While both films share a premise and familiar elements, they could not be more unique from each other in terms of style and execution. WILD SEARCH feels like the rambunctious little brother to the more dour WITNESS. It can be a little silly and messy but it’s a lot of fun to spend time with.

The cover for the 1990 laserdisc of WILD SEARCH

The cover for the 1990 laserdisc of WILD SEARCH